Sri Lanka’s government is heavily burdened by foreign debt payments, and a current account deficit that pressures the national currency, the rupee.

Where Is Sri Lanka? What Are Its Demographics

Sri Lanka is an island nation in the Indian Ocean, and it’s off the southeastern coast of the Indian subcontinent. In an area of about 25,000 square miles (slightly larger than West Virginia), its main sources of income from exports are textiles, garments, and tea leaves.

Out of a population of 21 million people, about 8.2 million are employed, with a quarter working in agriculture. The country’s population is rapidly aging, with the number of elderly people (65 and older) predicted to reach 25.7 percent of the population by 2050, compared to 13.4 percent in 2015.

An Overview of Sri Lanka’s Economy

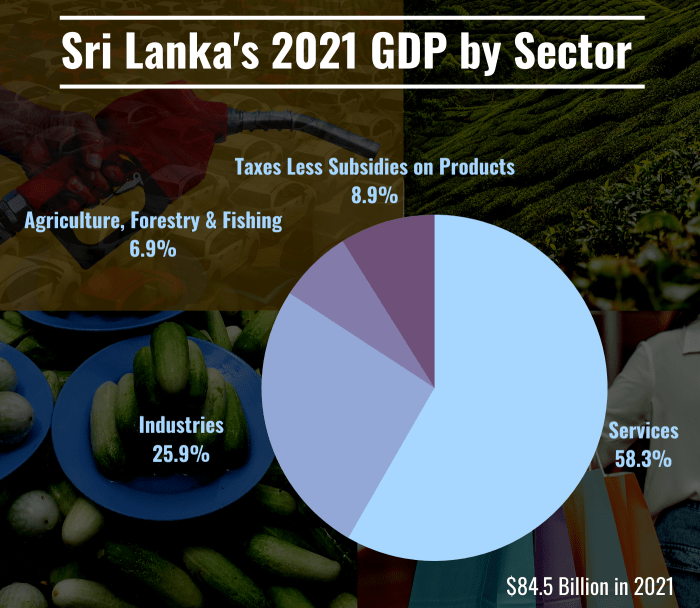

Sri Lanka’s economy was valued at $85.2 billion in 2021, holding steady from previous years in spite of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on tourism, one of its biggest contributors to earnings. Breaking it down by sector, services accounted for more than half of gross domestic product at 58.3%, followed by industries (25.9%); agriculture, forestry and fishing (6.9%); and taxes less subsidies on products (8.9%). In 2021, foreign debt totaled around $35 billion.

Economic Background

Starting in the 1970s, Sri Lanka started to liberalize its economic policies, and the government pushed for an open economy, in which goods and services would trade freely, and barriers to entry such as tariffs would break down. It wasn’t until after the end of the civil war in 2009, when the government defeated the Tamil Tigers—a separatist group seeking an autonomous state within Sri Lanka—that the economy started to gain momentum.

In the post-conflict era (after 2009), economic growth briefly accelerated, and per-capita income doubled. But not every aspect of the economy was moving strongly. Sri Lanka is a resource-poor nation, and its reliance on agriculture adds little value to the economy. For decades, the government has been running fiscal and current account deficits, which means that it has relied heavily on borrowing to finance government spending, at times taking out loans with particularly high interest rates.

These twin deficits have plagued the government’s ability to get itself out of debt. The government has for years mismanaged tax collection and provided few meaningful attempts to diversify and generate revenue. Remittances from abroad have helped to prevent the current account—the broadest measure of trade in goods and services—from widening. That secondary income accounts for a big chunk of GDP. The nation imports more than it exports, and the central bank has had to use up its precious stores of foreign exchange reserves to make payments on imported goods and servicing debt.

Political Background

In the post-conflict era, Sri Lanka had plenty of opportunities to build on the momentum of the end of the civil war to focus on economic development. The head of state, President Mahinda Rajapaksa, ruled from 2005 to 2015 and was credited with ending the decades-long internal conflict, but his government was plagued with accusations of graft, corruption, and economic mismanagement.

For example, his government increased its defense budget during peacetime rather than channel spending toward infrastructure projects. His family’s businesses were accused of benefiting from favorable government projects that could have gone to other contractors who had no ties to the president.

After Mahindra’s term, a new president helped to briefly put the budget in surplus. But Mahinda’s older brother, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, was elected and took office in November 2019, implementing a tax reform that lowered income tax rates on top earners and put the fiscal budget further into deficit.

What Caused Sri Lanka’s Economic Crisis?

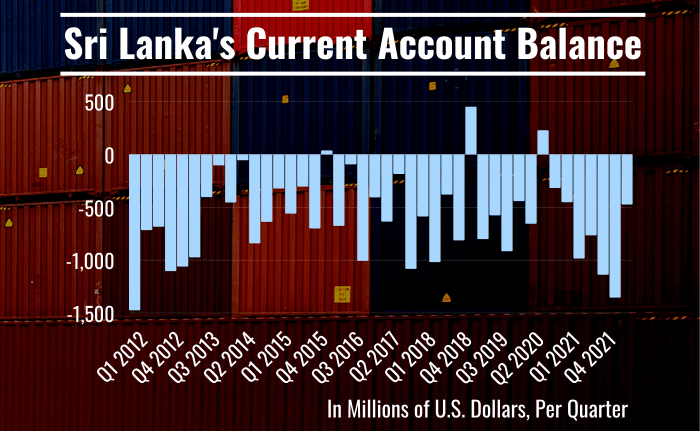

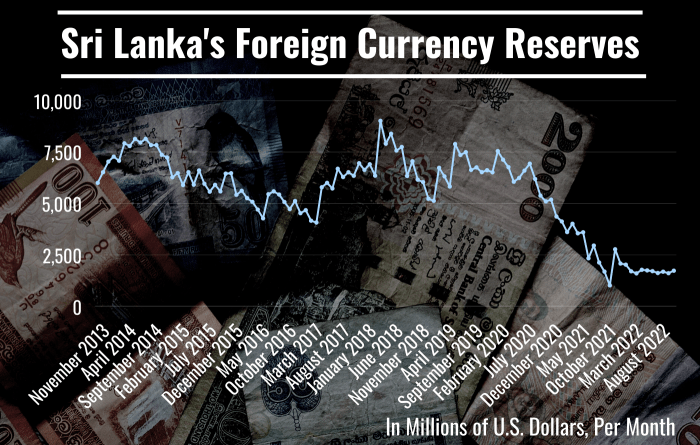

Many factors contributed to Sri Lanka’s economic collapse in 2022. When looking at a developing country’s ability to protect itself from shocks to the financial system, foreign exchange reserves are particularly important. A nation’s current account is also a leading indicator of economic growth and its currency. Examining Sri Lanka’s current account and foreign reserves can help to explain what led to the country’s economic decline.

Current Account Deficits

Sri Lanka has been facing deficits in its current account for decades, partly due to the government’s inability to diversify sources of income. Its main exports are textiles, garments, and tea leaves, and the nation has little manufacturing output.

Services remain the biggest contributor to GDP, but a quarter of Sri Lankans are disproportionately employed in agriculture. The government has relied on importing more goods than it can export, putting the nation’s current account persistently at a deficit.

In the graph below, Sri Lanka has experienced only a few quarters of surpluses from 2012 to the second quarter of 2022. Financing the deficit usually means borrowing from abroad to cover the shortfall.

Foreign Currency Reserves

With the current account in deficit, foreign investors have little reason to hold onto Sri Lankan rupees. The country has had to exchange much of its own currency for dollars to pay for imported goods, and that has led to the depreciation of the rupee. Billions of dollars pour into the economy via remittances from Sri Lankans working abroad each year. Still, maintaining foreign reserves is a challenge due to the pressures of foreign debt repayment, which is typically in dollars, and payments for imports, such as gasoline, other crude oil fuel products, and fertilizers.

In the graph below from November 2013 to November 2022, monthly reserve levels reached a peak of $9 billion in April 2018 before gradually dropping to a low of $1 billion in November 2021.

Foreign currency reserves started to decline in mid-2020, when nationwide lockdowns and a halt in global trade pushed the central bank to dip into reserves for payments.

COVID-19: A Turning Point in the Economy

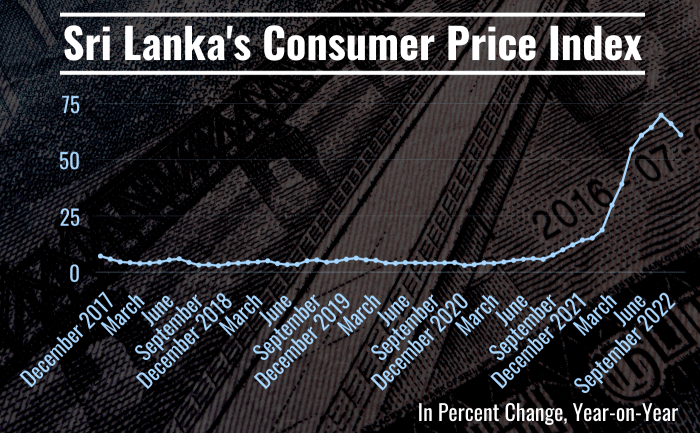

The COVID-19 pandemic upended Sri Lanka’s economy, further complicating the nation’s finances and ability to make payments. Inflation started to creep up in 2021 amid supply-chain disruptions, and maintaining foreign reserves became difficult due to a drop in tourism and declines in remittances.

The consumer price index, an inflation benchmark, increased at a more than 10% annual rate beginning in December 2021 (eventually topping at almost 70% in September 2022). To rein in runaway inflation, the central bank started to tighten monetary policy in early 2022 aggressively, and the resulting rising interest rates would have a detrimental impact on lending—squeezing businesses out of their ability to borrow to finance their operations, and, in turn, curbing economic growth.

Inflation quickly accelerated on an annualized basis from late 2021, highlighting the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic a full year in.

Acceleration Into Economic Collapse in 2022

Social unrest began to emerge in the form of public protests in early 2022. The government attempted to quell protests by banning social media, declaring a state of emergency, and setting curfews, but these efforts were futile.

With foreign reserves at their lowest levels in years, the government had little funding to help pay for goods from abroad, notably fuel. Long queues started to form at gasoline filling stations, and power outages became common, affecting businesses and their output.

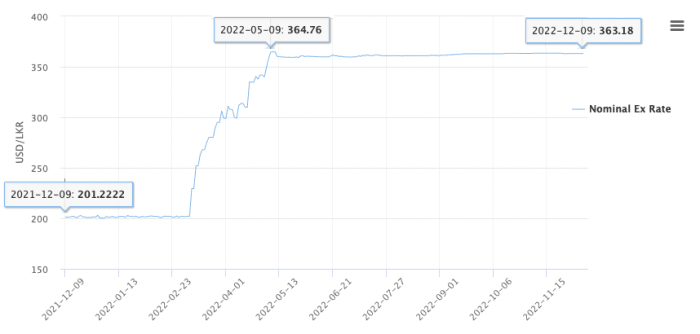

In March 2022, the central bank abandoned hopes to protect the rupee from further depreciation, setting the currency into freefall. In April, the government—with foreign reserves hovering just above $1 billion and few funds available to make payments—stopped serving its overseas debt, pushing the country toward default. By May, a dollar fetched about 365 rupees, compared to about 200 rupees two months earlier.

After the rupee’s sharp depreciation, the IMF started to intervene to help save Sri Lanka’s economy from further collapse.

The public called for Gotabaya Rajapaksa to step down as president, which he did in July. A new president was in power, but financial problems persisted, and the government was too broke to deal with them.

The International Monetary Fund stepped in and served as a lender of last resort by providing a $2.9 billion loan to Sri Lanka in September to help the country meet its payments. The emergency relief, though, came with certain conditions for economic reform, including changing the tax structures to collect more income and improving fiscal transparency.

Can Sri Lanka Recover From Its Economic Crisis?

With the IMF’s relief package and austerity measures in place, Sri Lanka can begin navigating its path to economic recovery. Many other countries have faced similar hardships, and in most cases, it took years to right their economies.

One of the benefits of a depreciating currency is that Sri Lanka’s goods and services become cheaper to buy in terms of foreign money, and that might help to steer the current account into surplus. Diversifying its economy to include other forms of revenue generation could become a priority under the IMF economic reform plan.

Still, challenges remain on the political front, and much depends on political leaders’ willingness to change. Whether the new government will deviate from past policies under previous administrations remains to be seen.