About $300 billion may have left China in the past two years in ways that are not captured by conventional balance of payments statistics. That flow would have been large enough to have had a substantial impact on foreign financial markets—and calls into question the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) recent judgment that the country’s “external position in 2022 is broadly in line with the level implied by medium-term fundamentals and desirable policies.”

According to China’s State Adminstration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE), Chinese residents spent $107 billion less than they earned in 2022Q4, for a total current account surplus of $418 billion for the full year of 2022. That is up from $317 billion in 2021 and on par with the previous peak hit in 2008 ($421 billion). China’s economy and the world economy are both much larger now than then, which may explain the IMF’s sanguine attitude.

However, as I have repeatedly pointed out, the official balance of payments numbers are…unusual. The latest data suggest that China’s current account surplus was $100 billion larger (36%) in 2021 than officially reported and $200 billion larger (48%) in 2022—with corresponding implications for net financial flows out of the country to the rest of the world.

When I last dug into this issue in October, I pointed to two separate issues.

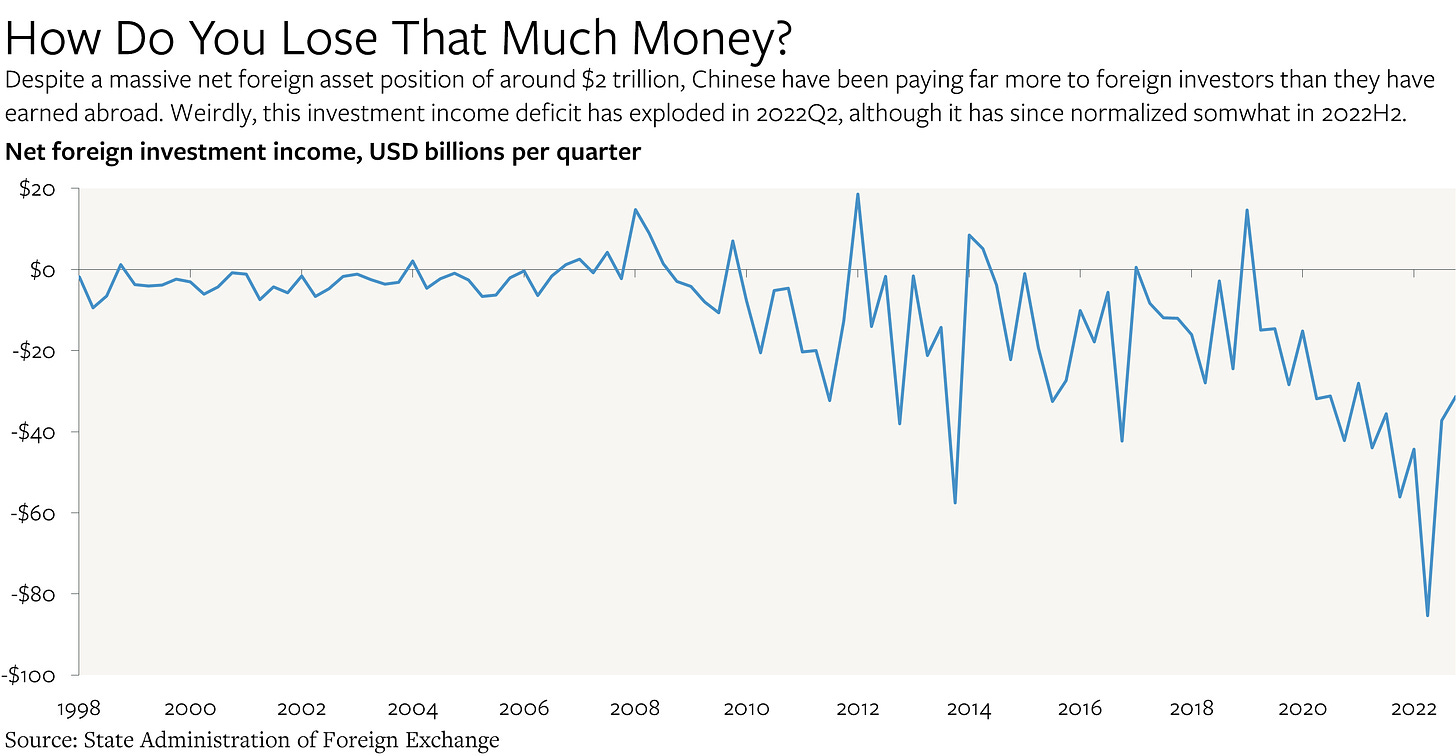

First, there was the surge in China’s investment income deficit since mid-2021. That seemed odd given the country’s substantial net foreign asset position, as well as the moves in relative interest rates, which should have lowered payments to foreigners even as higher yields flowed through to Chinese fixed income investments abroad. Tellingly, both Chinese and foreign investors responded as would have been expected, with substantial net bond flows into China in 2020, modest net flows in the first half of 2021, and massive net outflows in 2022 (as of Q3, latest available data).

The good news—at least for those us with a compulsion for getting the numbers to line up—is that China’s investment income balance has normalized somewhat after the weird behavior in the first half of 2022.

Unlike many other statistical agencies, SAFE does not provide any kind of geographic or asset class breakdown explaining what might be driving changes in investment receipts and payments. While it is likely that foreigners’ investments in China yield substantially more than Chinese investments abroad, it is unclear why the relative yields would have moved so much so recently when the net foreign asset position has not changed very much in the past six years.

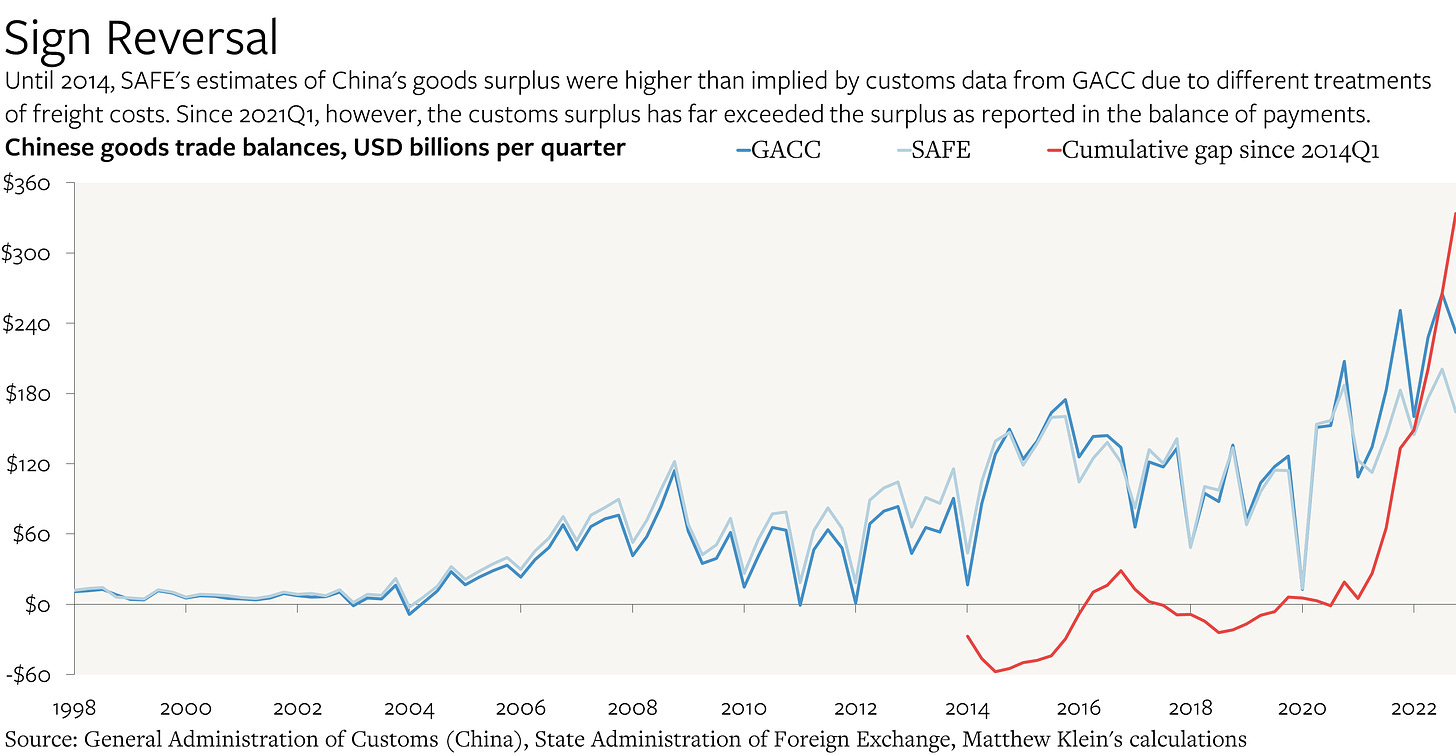

The other—and more important—reason to think that China’s current account surplus may be under-reported is that the goods trade surplus according to SAFE is far smaller than the goods trade surplus according to China’s General Administration of Customs (GACC). These measures have never lined up perfectly because of definitional and methodological differences. Historically, the SAFE estimate of the surplus was slightly higher than the GACC estimate because of how they treated freight costs. Over time, the two estimates convereged and were remarkably close in 2014-2020. The recent discrepancy is both enormous and extremely unusual.

Most of the recent discrepancy is attributable to different estimates of exports earnings. SAFE’s estimates of imports as reported in the balance of payments have increased relative to the GACC estimates, but not by very much. By contrast, SAFE’s estimates of exports have grown far less than the GACC measure.