Natasha Shah and her husband were thrilled to be buying their first home, an apartment off the plan in a welcoming Perth suburb.

The experience with a property investment advisor had been smooth, the conveyancer was on board, and the mortgage broker was ready to sign them up for a competitive loan.

Then, as she was working through the application in the Middle Finance app, Shah came to a section titled ‘banking details’ – into which she was instructed to enter her internet banking ID and password.

“When people mention ‘banking details’, all that I would normally expect it to be is a BSB, account name and number,” she recalls.

“I’m quite used to providing these.

“But then it said ‘password’ and that’s when I started to just freak out.”

With good reason: in a world where even relatively innocuous personal details have become valuable commodities and data breaches of financial providers, real estate agencies see the details of millions hawked on the dark web for peanuts, handing over control of your bank accounts to a third party – even if it’s to help substantiate your mortgage application by providing details of your expenses – feels to many like crossing a red line.

It’s also likely to land you in hot water with your bank: “one way you can help us [secure your details] is to make sure you never share your NetBank password with anyone,” the Commonwealth Bank of Australia advises, “including third party apps or services… the safest apps and services will never require you to enter your NetBank password.”

Sharing your password with someone – even a broker – means your bank won’t cover you if something goes wrong. Photo: Shutterstock

The NAB is equally concerned about the practice, bluntly advising customers “don’t share passwords, ever.”

“One of your responsibilities as a NAB account owner and user of internet banking is to protect your password,” that bank advises.

“Sharing your password or PINs may affect a claim for any money lost due to fraud.”

Scraping the bottom of the barrel?

Despite banks’ very clear warnings, mortgage brokers – along with many other financial service providers, such as payday lenders and investment apps like Raiz that access your accounts to monitor and report on your spending habits – continue to demand banking passwords as part of their normal onboarding processes, which typically require them to provide banks with detailed summaries of your last six months’ worth of spending.

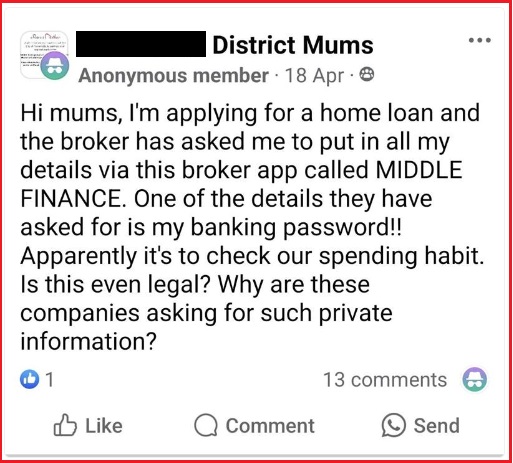

Reluctant to just blindly give in to something she wasn’t comfortable with, Shah – who has previously bought properties in Malaysia, where the brokerage and loan process is handled face to face with paper documents – began investigating the practice and posted a question on a mum’s Facebook group she frequents.

The message Natasha Shah originally posted on a mothers’ group message board. Photo: Supplied

“A bunch of mums said that yes, this is normal,” she said.

“It may be normal to them, but it’s not normal to me.”

Her broker was ultimately happy to let her supply download PDF statements from her online banking, but not all brokers or banks will accept them: such files aren’t always trustworthy because they can be – and often are – easily edited.

“If you’re going to send a PDF statement, there’s no real way, without being able to read the metadata, that you can confirm it’s real,” said Sam Roby, a finance broker with JustFin who sees real value in screen scraping services that both make expense reporting “substantially easier to read”, and ensure that clients aren’t misrepresenting their financial situation.

Broker Sam Roby of JustFin. Photo: Supplied

“Everyone always conveniently forgets to mention a couple of credit cards,” Roby laughed, adding that he has seen many times where “people are absolutely trying to sneak one past you.”

And while some people balk at signing up through the screen scraping services, he said, “most find that [compiling the data manually] just gets too hard and they do the link”.

“You can always just change your banking password 30 seconds later.”

To be clear, brokers are not collecting your banking passwords or writing them on sticky notes at their offices: they typically send you a link to log onto a third-party service like Illion’s BankStatements.com.au, CashDeck, Basiq, or Envestnet’s Yodlee, all of which use a technique called ‘screen scraping’ to log onto your bank account, then download details of your spending and other transactions.

Those services use encryption to protect your password details, then delete those details once they have downloaded the spending details they require.

They also provide brokers with analytics services, automatically scanning your spending and providing a categorised summary to save brokers a considerable amount of time in preparing your application.

“The process is very safe and was reviewed by our aggregator AFG before we were allowed to use it,” Nicole Cannon, founder and director of Pink Finance, told Information Age.

Broker Nicole Cannon of Pink Finance. Photo: Supplied

“It is actually safer to send via the CashDeck portal than it is to individually download statements and email them to us due to the encryption security they use,” Cannon regularly advises her clients.

“If you send your personal information via email, we cannot guarantee the safety of your information.

“We strongly encourage and support the protection of your information through using the CashDeck portal.

“It ensures we get six full months of statements and it doesn’t have any gaps.”

“We now give priority to those who use the portal.”

A better alternative is already available

It may seem innocuous to brokers, but for home buyers with hundreds of thousands of hard-earned savings in the bank, handing over the keys to that money – which could be quickly transferred to other accounts, then converted into cryptocurrency and never seen again – flies in the face of everything we have been told about protecting our personal data.

In a world where banks are under constant cyber attack and the government is all but begging Australians to be more careful with their personal information – and suing companies for hundreds of millions of dollars when they neglect to do the same – the widespread use of screen scraping remains a bugbear for security practitioners.

Concerns about the practice were significant enough that the government last year completed a formal inquiry into the practice and its policy and regulatory implications – and last year released a discussion paper that concluded asking customers for banking passwords “runs counter to IT security practices, advice provided by the Australian Government, banks’ terms and conditions, and MyGov’s Terms of Use.”

In desperation to secure a home loan, buyers are handing over online banking details to mortgage broker apps. Photo: Shutterstock

“Consumers may not always understand when they are using services that rely on screen scraping, nor the consequences of doing so and any associated risks,” the report observed, noting that providing account login details means that consumers “may have little control over what specific data and access the third party may have and how they consumer can end the arrangement.”

“Against a backdrop of heightened security awareness, it may be difficult for some consumers to navigate what actions are right for them if they are given mixed messages about the risks associated with sharing their login details.”

Here’s the kicker

A much more secure, more capable alternative has already been available for years – but almost nobody knows about it, and even fewer people are actually using it.

That alternative is open banking, a high-level concept in which financial services institutions smoothly and securely exchange customer data in standard formats that make it easier to switch banks, provide historical data for approvals, and engage new-age fintechs such as Raiz and Bamboo, which automatically buys tiny amounts of Bitcoin for you based on rounding up your spending.

Open banking isn’t exclusively an Australian concept – similar initiatives are operating around the world – but the way it is implemented varies from country to country.

In Australia, the facilitator of open banking – and similar strategies in the utilities and eventually the telecommunications industries – is Consumer Data Right (CDR), a far-reaching technology framework that works like plumbing for your data, securely moving it from one provider to another without spilling a drop.

CDR was passed into law in 2019 and came into effect in mid-2020, with enabling legislation requiring banks to share data about mortgages and personal loans from November that year.

Administered by the ACCC, CDR requires banks and other financial institutions to comply with CDR Rules and technical standards set by the Treasury’s Data Standards Body (DSB) that let you not only authorise the transfer of your data, but to specify which data can be shared and which cannot.

You can authorise a third party to access data on your behalf, and you can revoke access at any time before CDR authorisations automatically expire after 12 months.

A matter of awareness, not capability

CDR has proven to be a game-changer for fintechs like UpWorth, which maintains a 360-degree view of customer accounts, superannuation, cryptocurrency accounts and other instruments so it can recommend ways to get better returns.

And while the company relies on screen scraping to access accounts where CDR isn’t available, Upworth cofounder Maxime Chaury told Information Age that open banking is the preferred option in the long term.

Upworth cofounder Maxime Chaury. Photo: Supplied

“CDR is better than screen scraping,” he explained, noting that “some companies are trying to prevent screen scraping – so when the website changes, there are bugs and issues when extracting the data, whereas CDR will always be available.”

“We are actually audited by third parties and working with the ACCC to make sure that we respect all the data security, data privacy, and cybersecurity rules set by the CDR regime.”

So, if CDR is already capable of enabling the same functionality that screen scraping, but can do it without requiring you to hand over your banking password, why are brokers still directing clients to screen scraping services?

The answer became clear after a recent strategic review – which was conducted by Accenture and commissioned by the Australian Banking Association (ABA) – found that not only is almost nobody using CDR, but that half of those that have used it have never used it again.

Despite the industry investing $1.5 billion to build and deploy CDR since 2018, the report found that just 0.31 percent of bank customers were using CDR by the end of 2023 – leading ABA CEO Anna Bligh to call time on a project that simply hasn’t cut through into the public awareness.

Australian Banking Association CEO Anna Bligh. Photo: Supplied

“Australians have enthusiastically embraced digital innovations in banking such as mobile wallets and PayID,” she said in releasing the CDR review, “however uptake of the CDR has been comparatively low.”

“It’s time to go back to the drawing board.

“The current CDR regime isn’t delivering for customers or enhancing competition, and a new pathway forward is needed.”

CDR is actually causing problems for the industry, the report also found, since its high implementation costs are preventing banks – particularly smaller banks – from investing in other technological innovations that could benefit customers even more.

“While we support the intent of the CDR to increase competition,” Customer Owned Banking Association (COBA) CEO Michael Lawrence said, “it has actually made it more difficult for smaller banks to compete by tying up resources with little to no tangible return.”

“Before smaller banks commit more resources, we ask for a clear roadmap to ensure the CDR delivers on its original intent to improve competition.”

COBA CEO Michael Lawrence. Photo: Supplied

Screen scraping’s days are numbered

It may get the job done, but the way screen scraping is administered “is pretty bad practice” in terms of privacy and consumer consent, Jill Berry, CEO of CDR intermediary Adatree, told Information Age.

Although they are “technically accredited” for CDR, Berry said, companies like Yodlee and BankStatements.com.au owner Illion “are not providing open banking or regulated data services” and remain focused on data collection and retention.

Such companies are more likely to be harvesting and, in the case of some companies, selling your personal data: even if you gave some of these companies your bank details years ago, Berry said, “to this day they would still be collecting, harvesting, and onselling your data, and you would have no clue – and the only reason that it would stop would be if you change your password.”

Adatree CEO Jill Berry. Photo: Supplied.

CDR’s low adoption may well be due to the fact that many consumers are far less concerned about switching providers than open banking’s proponents believe – taking a set-and-forget approach to their finances and only studying the market for alternatives when they sporadically take out mortgages or finance.

Many are just focused on getting the job done: “bank statements are significantly important to brokers in order for them to understand their clients’ financial position, to meet their regulatory obligations and to ensure they are providing their customers with the most suitable loan which is in their best interest,” noted a spokesperson for the Mortgage and Finance Association of Australia.

“The Consumer Data Right will, in time, provide a more secure alternative for broker clients to share necessary data with their mortgage broker.”

Well aware of the need to reset the CDR narrative, Minister for Financial Services Stephen Jones – who was last year advised that screen scraping should be banned where CDR is a viable alternative – is said to be on the cusp of doing just that.

Such a ban would not only bring Australia in line with European jurisdictions that banned screen scraping years ago, but would provide impetus for Australia’s banking, financial services, and fintech industries to give their customers clearer guidance about how to provide the information they need to get a loan.

Consumers should look for the best home loan deal they can get without compromising their banking password. Photo: Shutterstock

“There’s an overall vibe that we need to grow and get better,” Chaury said, noting that “the missing piece in the conversation is that there is not enough actual reflection around what open banking is and what is its purpose.”

“It’s basically to bring back power from the big players, back to the consumers – which is why banks’ interest is to make it as overwhelming and complex and Byzantine as possible, so that people get overwhelmed and then just take whatever they are offered.”

The whole idea of open banking is that it’s easier and less worrying for customers, Berry said: “with open banking, consent might only take 20 seconds, but you still get reminders about it. There are no dark patterns trying to coerce someone into consenting your data.”

“With screen scraping you have no information about who’s doing what with your data, for how long, and how to stop it.”

“You’re only ever one hack away from millions of Australians having their banking usernames and passwords stolen.”

Additional research by Roulla Yiacoumi.