When TD Kundan migrated to Surabaya in present-day Indonesia in 1931, he could not have foreseen what life had in store for him. Like other Sindhis in Surabaya, Kundan had wanted to be a trader – to set up his own business and tend to his family.

But within decades, his name was etched in the history of the city as a representative of the Indian community, a mediator between the British and the Indonesians, a bridge between Indonesian and Indian leaders, a facilitator of international aid, and most importantly, a peace broker and then a fighter in the famous Battle of Surabaya in 1945.

For this prolific service, Kundan was awarded one of Indonesia’s highest civilian honours. His contemporaries in the Indonesian freedom struggle glowingly attested to his stellar role. When he died, some of his remains were interred in the Memorial Cemetery of Heroes at Surabaya.

Western writers and historians did not acknowledge his story. It was first recorded by PRS Mani, an Indian reporter embedded in the British army’s 23rd Infantry Division. An Australian historian, Heather Goodall, detailed the picture in her 2018 book Beyond Borders: Indians, Australians and the Indonesian Revolution 1939-1950.

Community’s representative

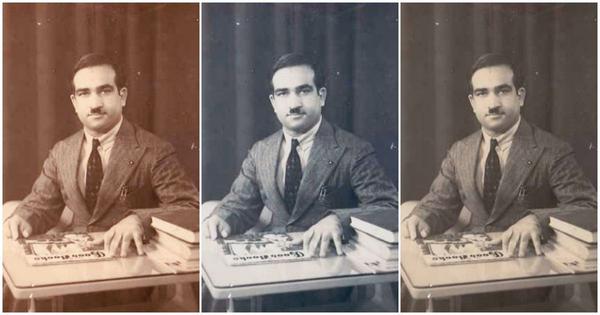

Thakurdas Daryanani Kundan was born in Hyderabad, Sindh, in 1911. A graduate of the University of Bombay, he earned a degree in philosophy and married in 1926. Five years later, he moved to Surabaya in the Dutch East Indies to set up a textile and trading firm with his brother. They called it Kundandas Brothers.

Kundan’s arrival in the Dutch East Indies coincided with a time of considerable political churn. The Dutch, who had colonised the region since the early 19th century, were facing growing pro-independence calls from groups such as the Budi Utomo, Indonesian National Party, Sarekat Islam and Indonesian Communist Party. For these groups, there were two means to get to their goal of freedom: accommodation or violence. A third way – non-cooperation – gained prominence in the 1940s with the rise of influential leaders like Sukarno, who would go on to become the first president of independent Indonesia, and Mohammad Hatta, who would be his deputy.

Meanwhile, in Surabaya, Kundan was emerging as a representative of the Indian community. He had a great facility with languages, he was the president of the Indian and Sindhi merchant associations, and his sprawling store in central Surabaya’s Tunjungan business district received visitors from all communities.

The Dutch took note of his ascendance and recognised him as a spokesperson of the Indian community. But while they were still dealing with the nationalists, the Second World War broke out. The Japanese, claiming to be the Light of Asia, swept out the Dutch in 1942 and established their own rule.

That reign lasted for three years. Within days of the Japanese surrender in the Pacific on August 15, 1945, Indonesian nationalists declared their country free, only to have British troops march in to restore Dutch colonial rule.

The 23rd Infantry Division, with its British Indian soldiers commanded by Brigadier AWS Mallaby, arrived in Surabaya on October 25 to oversee Japanese surrender and the rescue of Dutch and Eurasian war prisoners. By this time, Surabaya had got a temporary Indonesian administration that included Komite Nasional Indonesia as well as a security organisation called Badan Keamanan Rakyat.

There was volatility in the air. Armed militias patrolled the streets.

In this febrile environment, Kundan’s fluency in English and other languages made him a valuable mediator for both sides. Although the British and the Indonesians resented each other, they trusted him enough to let him interpret statements, carry messages, answer letters, negotiate movements and keep talks going.

“The British were surprised that Indonesia had their own English mastering freedom fighter,” wrote Ruslan Abdulgani, a nationalist leader who later served in Sukarno’s Cabinet. “Mr. Kundan’s English was excellent, sometimes poetical.”

In the first few days after the British troops’ arrival, he tried to maintain peace by imploring them to limit themselves to the port and dock areas. He would broadcast appeals for peace in Hindustani over Radio Pemberontakan in order to reach the British Indian troops directly. He knew many British Indian soldiers were already sympathetic to Subhash Chandra Bose’s Indian National Army and the Indonesian freedom struggle, which mirrored India’s own fight for independence. In Surabaya, graffiti had appeared on public walls and buildings calling for Merdeka (freedom) and Azadi ya Kunrezi (freedom or bloodshed in Urdu).

Kundan was present at a meeting in which Mallaby promised that the British would not ask Indonesians to hand over their weapons. But, as it happened, leaflets were airdropped over Surabaya on October 27, ordering its populace to disarm and surrender. This betrayal infuriated the Indonesians, who were already displeased at the reported presence of the Dutch among the British troops and interpreted it as an attempt to restore Dutch role in the islands.

Street battles broke out in no time. Alarmed at the worsening situation, Kundan made a desperate call to Sukarno, who was by now Indonesia’s president, and mediated a ceasefire on the night of October 28. For a while, there was peace.

But the lull was shattered when Mallaby was killed on October 30 (how and by whom is still debated). A vengeful British military launched a bloody onslaught on Surabaya. Additional brigades were called in along with Sherman and Stuart tanks, naval cruisers and three destroyers. Half of the city fell under the assault within three days, but the rest fought on.

On November 10, a day now remembered in Indonesia as Heroes’ Day, British troops began advancing “through the city under the cover of naval and air bombardment”. “Surabaya had turned into an inferno,” Abdulgani wrote later.

By November 29, the fighting was over. The British had won. Estimates say between 6,300 and 15,000 Indonesians died in the battle and another 200,000 were made to flee their homes. Confirmed British Indian fatalities numbered in the hundreds.

Kundan, as Abdulgani wrote, had joined in the battle after ensuring his family’s safety. But as the British forces took control of the city, he escaped, along with others, for the more secure highland towns of Lawang and Malang.

Rice diplomacy

Never deracinated from the country of his birth, Kundan also served as a vital link between the Indonesian independence movement and the leaders of the Indian National Congress, especially Jawaharlal Nehru. “Short-statured and well educated, Kundan had some links with the Indian national movement, and broadly sympathized with the struggle for Indonesian freedom,” PRS Mani wrote. “Besides moral support, he (and other Sindhi merchants) also gave generously to Sukarno and his associates.”

Some of those words of Mani ended up applying to him too. He left the army in 1946 and returned the very next year to Indonesia as a reporter, filing reports that brought Indonesian leaders – Sukarno, Hatta and Sutan Sjahrir – closer to the Congress leadership, including Nehru, Mahatma Gandhi and Maulana Azad.

In April 1946, Mani and Kundan facilitated the “rice diplomacy” efforts between Indian and Indonesian leaders to cement bilateral ties in a post-war world. A famine-struck India was offered 500,000 tonnes of rice by Indonesian Prime Minister Sutan Sjahrir. In return, Indonesia asked India for textiles, medicines and machine tools.

Kundan was appointed “Chief Agent” by the Indian government to coordinate the delivery of textiles and rice. He travelled to India in 1946 to secure these commodities, while serving as an emissary between Indian and Indonesian leaders, carrying letters and, on one occasion, books from Nehru to Sukarno.

The rice offer was resisted at every step by the Dutch, but, as Mani wrote, “By early June 1946 the Indian Government assembled its ships in Singapore in readiness for loading rice at Indonesian ports. And finally, on July 27 by which time all hurdles had been crossed, the Indian Food Secretary signed and exchanged letters of agreement with Premier Sjahrir.”

Four ports in Java were identified for the transfer of the shipment. But as Indian vessels made their way to Java, they were bombed by the Dutch. The inhumanity received widespread condemnation from the international community – even the British, who were still allies of the Dutch, had to criticise it.

For the next few years, the Indonesians fought determinedly for their freedom. The Battle of Surabaya had sparked a national revolution that refused to peter out. Finally on December 27, 1949, after a prolonged period of hostilities, negotiations and UN mediation, the Dutch transferred sovereignty.

After World War II, Kundan was awarded a medal by the British for his services as interpreter. In 1977, he was conferred the Nararya, a class of the Star of the Republic of Indonesia, one of its highest civilian honours. He remained in Surabaya till his death in 1980.

Some of his ashes are interred in the Memorial Cemetery of Heroes at Surabaya, his name alongside others on the Wall of Heroes. Indonesia’s relations with India chilled during the 31-year rule of General Suharto – a time when minorities and communists were oppressed – but, despite the events, Kundan remained “an ambassador for and of a multi-faith and transnational Indian community”.

The writer wishes to thank Heather Goodall, Professor Emerita of History at the University of Technology Sydney, for her generous inputs and suggestions.