Well-configured foreign currency and broader financial services sectors have a significant enabling impact on economic development. Current debates on bilateral currency trade, focused on geopolitical considerations, have missed the importance of the issue for smaller developing economies.

World-leading policies and initiatives in Africa are steering foreign currency exchange towards bilateral execution through a range of digital payment platforms. These will be economically beneficial to African countries and reduce the cost of trade, boosting development opportunities. This article provides a guide to how African countries have been looking to develop alternative ways to trade currencies. It spells out the advantages and disadvantages of the existing configurations used to trade currencies and their impact on the development prospects for countries like those in Africa.

It also touches on the role that the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) is playing in reconfiguring foreign currency trade, including Saudi Arabia’s role in driving the G20 to relook at the current foreign currency exchange architecture and the impact that BUNA, a real-time cross-border foreign currency payment system being rolled out across the Arab world, is likely to have across the Arab world, including those countries in Africa.

Why currency trade is important for development

The ability to pay for foreign-produced goods and services as well as source foreign capital for investment has been critical to the development of all economies and states for hundreds of years. To smooth the transfer of goods and services, a third asset (silver, gold, livestock, shells, large carved stones and recently paper and digital currencies) acts as the intermediary value to enable a transaction, allowing buyers and sellers to avoid bartering products. It is unlikely that the copper and iron age civilizations around Jebel Hafeet or Jebel Al Buhais would have existed without trade enabled by currency exchange (most probably silver or gold) with other civilizations across the Gulf region over 4000 years ago.

All modern market economies require even more inputs from other parts of the world than copper or iron age civilizations to maintain development and economic growth. The ability to buy and sell goods and services with other economies is enabled by a combination of financial services, including foreign currency payments and trade-related finance and insurance. These services have grown in complexity as traders’ understanding of risks improved and the demand for those products has boomed as underlying trade soared.

While economic theories have assumed efficient financial services intermediating currency and capital into a real economy, the reality is this could not be further from the truth. Financial intermediation is a substantial share of value added on its own, especially in advanced economies, implying that the intermediation of capital and currencies has a cost to economies.

Inefficient or ineffective financial services can therefore hinder trade through higher transaction fees and return hurdles for capital invested. Optimizing financial services to support real economic activity is an important issue, especially for poorer countries, which have limited access to capital in the first place.

The network of foreign exchange (forex) payment intermediaries and models may seem removed from the day-to-day activities of economies, but they are the largest marketplaces in modern economies in terms of value transacted.

Foreign currency trade was estimated to be a US$7.5 trillion per day market globally in April 2022.[1] For this service, currency intermediaries generated an estimated US$850 billion in direct revenues from the exchange of currency by 2024.[2] However, this excludes supporting financial services related to currency trade that occurred in the broader ecosystem of financial services that allow an economic actor to pay another actor in another market. The World Bank estimates that low-value remittances to emerging markets (the largest capital flow into Africa annually) cost 6.35% of the remitted value, many multiples of the actual underlying cost attributed to currency exchange.[3]

Translating this into value for a foreign currency exchange enabling businesses, the numbers continue to dwarf all others. For the largest foreign exchange correspondent bank, JP Morgan Chase (JPM), the value of foreign currency-related contracts they are exposed to dwarfs the combined value of major sovereign wealth funds (SWFs). At the end of the 2023 financial year, JPM’s foreign exchange-related financial contract exposure was US$13.6 trillion,[4] compared to total sovereign wealth fund assets of US$11.3 trillion in the same year.[5] For this, it earned just over US$5 billion in revenues, directly from foreign currency exchange activities, representing an extremely low margin when compared to the total flow of foreign exchange it intermediated. However, this underestimates the total value generated for financial services businesses.

Understanding the link between foreign currency exchange and other financial services

Trading goods and services typically experiences a delay between the purchase of the good or service and the consumption of that service by the buyer. Even as e-commerce platforms can deliver meals within the hour or consumer electronics within the day within local markets, as soon as any product is delivered from offshore, those timelines stretch into days and weeks.[6] Shipping products between South Africa and China, Africa’s largest trading partner can take up to 26 days. Including inland transportation legs of a week to transport copper from Zambia to South Africa, buyers face over a month of waiting for products to arrive. For buyers to be confident of receiving the product they bought and sellers to dispatch the product that they sold, a complex array of financial products has been developed to reduce non-payment risks.

Financial institutions intermediate the delayed payment for goods and services by offering trade finance and insurance that protect sellers and buyers from various risks and allow both to avoid having to make payment before the product is received by providing credit. Banks that service both buyers and sellers have been better positioned to manage the risks of financing the transaction. They are also better positioned to enable the currency exchange by having a pool of the two local currencies from which they use to enable a currency conversion.

Given how closely trade finance is linked to foreign currency flows, there are strong network effects that financial services operators can generate. In the case of JPM, being a large correspondent bank means it has been well placed to enable all the related local transactions from foreign currency trade as well as provide a range of products and services to its business clients. These range of services offered to both trading businesses and foreign and local capital markets investors earned JPM US$19.4 billion in 2023. It also contributed to the bank’s overall commercial and investment banking income, which reached US$64 billion.

Background to the current foreign exchange market

The invention of coins and paper money allowed states to issue their own legal tender, creating multiple currencies that needed conversion. In the last few hundred years, two currencies of value to buyers and sellers were exchanged at a pre-agreed conversion rate, sometimes intermediated by a third asset of value, gold. This third store of value enabled a trilateral exchange of currencies and allowed both buyers and sellers to avoid holding assets in currencies they did not need or want. After World War II, the U.S. dollar’s (USD) peg to gold was introduced with other currencies having a fixed (but adjustable) peg to the USD. The U.S. dollar acted as the intermediary value against which two currencies would be benchmarked, again enabling a trilateral exchange of currencies. Currency A could be converted into USD, which would then be converted into Currency B.

During this period, currency conversion to the USD could be managed by central banks.[7] The advantage of this system was that the USD offered the convertibility of one nation’s currency into any other that was pegged to the USD. Central banks then only needed to deposit assets (gold or dollar) in the U.S. to guarantee conversion with all other currencies. This gave the U.S. a huge advantage in accessing capital and trading goods and services.

To generate income from assets, Central Banks used their deposits to earn income, invariably through trading them on U.S. capital markets. This provided a boost to the development of U.S. capital markets, which remain the largest globally, 50 years after the end of the U.S. dollar-gold peg. When trading goods and services with the U.S., another country only needed to engage in a bilateral exchange of currency with the USD, thereby eliminating the second transaction leg into a third currency. This reduced the cost of foreign currency exchange.

As inflationary money printing by the U.S. and oil embargo-related economic shocks of the 1970s made the USD an unattractive intermediary of currency value, currency conversion using the USD was replaced by a range of other foreign currency marketplaces subject to greater or lesser intervention by each economy’s currency producers and intermediaries. National central banks and correspondent banks acted as intermediaries between buyers and sellers of traded products and services and the foreign currency payments infrastructure. Currency markets in the UK, France, Switzerland, Germany and Japan offered the convertibility of currencies using the currencies of those markets, rather than the USD. The advantage was now that countries trading with those other large trading markets could execute bilateral currency transactions, and potentially also offer a competing foreign currency market to the U.S. for other trilateral currency transactions.

For smaller emerging market economies looking to trade amongst themselves, trilateral exchange using the UK Pound, French Francs, or German Deutsche Marks just replaced USD. The system of exchange remained essentially the same, now with a bit more competition and a higher proportion of bilateral currency transactions with those other foreign exchange marketplaces.

However, as the U.S. stabilized and the Cold War ended, the USD has played a growing role in the currency exchange market. Foreign currency exchange was opened to competition, allowing a range of different payment systems, but the USD has remained preeminent. Reasons for this concentration have centered around businesses operating in increasingly complex and long global value chains across multiple markets requiring a common currency in which to compare costs and profits.[8]

From a financial perspective, the USD has also been an attractive store of value that is both relatively stable, freely convertible and offers a range of sufficiently attractive, predictable financial returns to allow banks and other foreign currency participants to deposit collateral needed to trade globally.[9] However, even before geopolitical tensions rose, there was a rising discontent with the current system from large emerging market economies like China and Russia. African markets were also working on hedging their bets.

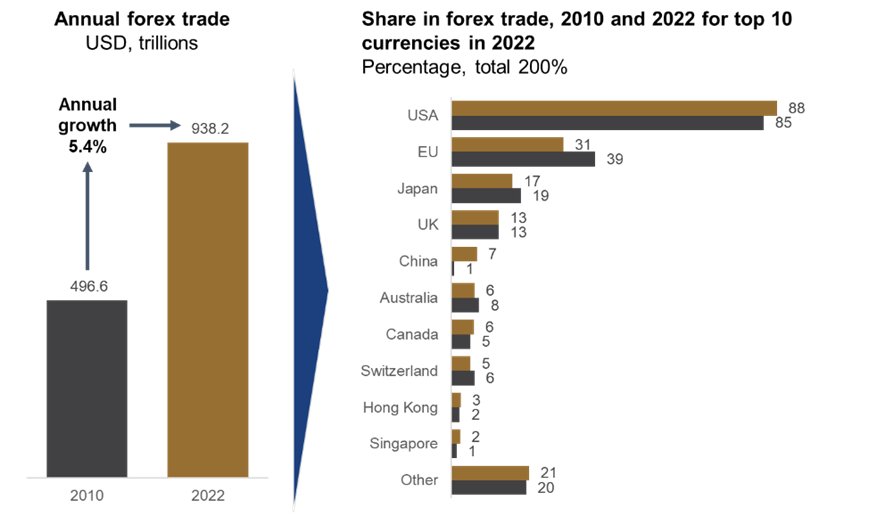

The introduction of increasingly onerous Know Your Customer and Anti-Money Laundering (AML) standards introduced around periods of geopolitical instability or terrorism have also raised the risks of using trilateral currency exchange using a rival’s currency to trade with the rest of the world. However, by 2022, the USD was involved in 88% of currency trades globally (on a gross basis), up from 85% in 2010, even as global foreign currency trade grew from ~US$500 trillion to over US$938 trillion over the same period and emerging markets’ share of the global economy increased.[10]

Figure 1: Foreign exchange trade

Source: Bank of International Settlements (BIS), https://www.bis.org/statistics/rpfx22_fx.htm

Recently, bilateral currency trade attracted attention when Russia’s war in Ukraine showed how far G7 countries were willing to apply sanctions on financial flows to Russia and their supporters by restricting access to G7 currencies and global payments enablers, like SWIFT. These sanctions had an immediate impact on how Russia made and received payments for its trade activities, resulting in a scramble to find alternatives to global financial services payments utilities they were no longer able to use.

Bilateral currency exchange was the quickest way for Russia to avoid trilateral currency exchange using G7 currencies, which were now off limits. But it came with its own constraints as lopsided trade flows with key trading partners (like India) created a buildup of foreign currency locked up in the trading partners’ banking systems, with no way to repatriate the benefits, without dramatically impacting the prevailing exchange rate, or violating India’s tight capital controls.

Sanctions also highlighted the reliance on tri-party currency transactions using USD, Euros (EUR), Japanese Yen (JPY) and UK Pounds (GBP) to match payments between smaller economies’ currencies to effect global trade. In the Bank of International Settlements’ (the Central Bank to sovereign Central Banks) most recent foreign currency market survey in 2022, USD, EUR, JPY and GBP were involved in ~74% of currency transactions (on a net basis), down slightly from 78% in 2010.

Technology and economic drivers for bilateral currency exchange

The process of China and Russia diversifying away from G7 currencies to enable trade has coincided with a growing pressure on the existing forex architecture to change since the turn of the century.

Three trends have increased pressure for the existing foreign currency market configurations to be updated:

- The digitization of financial services created opportunities to:

- Accelerate the speed at which foreign exchange could be transacted, thereby reducing the amount of collateral needed to guarantee the conversion of currencies at a later date.

- Reduce the cost; digitally enabled transaction messaging costs can be delivered.

- Increase price transparency through the publication and aggregation of price data from multiple local foreign currency markets, globally.

- The emergence of more efficient informal currency trading platforms enabled by blockchain technologies, which have

- Provided an alternative trilateral currency to match currencies, such as Bitcoin or the initially tongue-in-cheek Dogecoin.

- Highlighted the redundancy of existing capital-intensive delayed clearing and settlement payment platforms that required banks to deposit collateral against future foreign currency payment obligations that are a hangover from the days of paper-enabled transactions.

- Avoided the regulatory compliance overhead within regulated payment channels.

- Helped digitize and scale up black markets for foreign currency that have been a feature of many restrictive emerging market currencies.

- The decline of the number of correspondent banks enabling cross-border currency trade, due to a range of factors, including

- The rising cost of compliance against a range of anti-money laundering and know your customer standards.

- Increased capital requirements from rising counterparty risks and the increasing complexity of foreign exchange markets, which have depressed earnings.

Instant payments impact on bank risk capital and collateral requirements

A key element critical for the cost of transactions is the reduction in the amount of pre-funding required to transact. In the past, banks would have needed to post funding equivalent to several days’ worth of transactions, with the introduction of trilateral transactions increasing the period between making a payment and receiving it even longer, resulting in even more pre-funding.

Correspondent banks had a network advantage by being able to post lower rates of pre-funding. Net settling of transactions where many small outbound transactions are bundled together and off-set against incoming transactions means that a fraction of foreign currency transacted can be moved from one market to the next. It also reduces the credit exposure between transacting parties, reducing the required capital needed to offset that exposure. Large banks with bigger networks and higher volumes of daily transactions generated the largest advantage from net settlement.

However, as the time between transacting and settling a foreign currency transaction becomes shorter through the application of Real-Time Gross Settlement digital payment systems for foreign currency payments, this advantage is disappearing. Banks acting on behalf of buyers and sellers now only need to supply enough funding necessary to settle transaction volumes over a day or even hours. Declining gaps between clearing and settlement allow banks to participate in cross-border payments more actively, as their exposure to foreign currencies has dropped, reducing the risk capital needed to enable a certain volume of foreign currency transactions.

Instant cross-border payments have generated a further advantage by reducing the need to select a stable currency in which to hold pre-funding, making unstable currencies relatively more useful if they are freely convertible. This is because banks can move funds received in return for exchanging their own currencies faster, reducing the need to generate incomes in that currency or buy expensive hedges to avoid losses from potential future devaluations of that currency.

The G20 response to a growing opportunity to reform foreign exchange marketplaces

In response to these building pressures on the existing payments architecture, the G20, encouraged by Saudi Arabia’s presidency in 2020,[11] agreed to investigate ways in which cross-border payments could be made more efficient and cheaper for users. This culminated in an undertaking to drive cross-border payment costs down to 1% for retail and 3% for remittance cross-border payment users by 2027.

Interestingly, in the wholesale market segments, dominated by the likes of JPM, a price benchmark has not been set, alluding to how difficult it has become for regulators and wholesale bank customers to understand what costs they face for foreign currency exchange services.

The status of foreign currency trade in Africa

Africa’s small economies are most in need of convertible currencies, as they are more likely to need goods and services from offshore markets when compared to larger, diverse, developed economies.

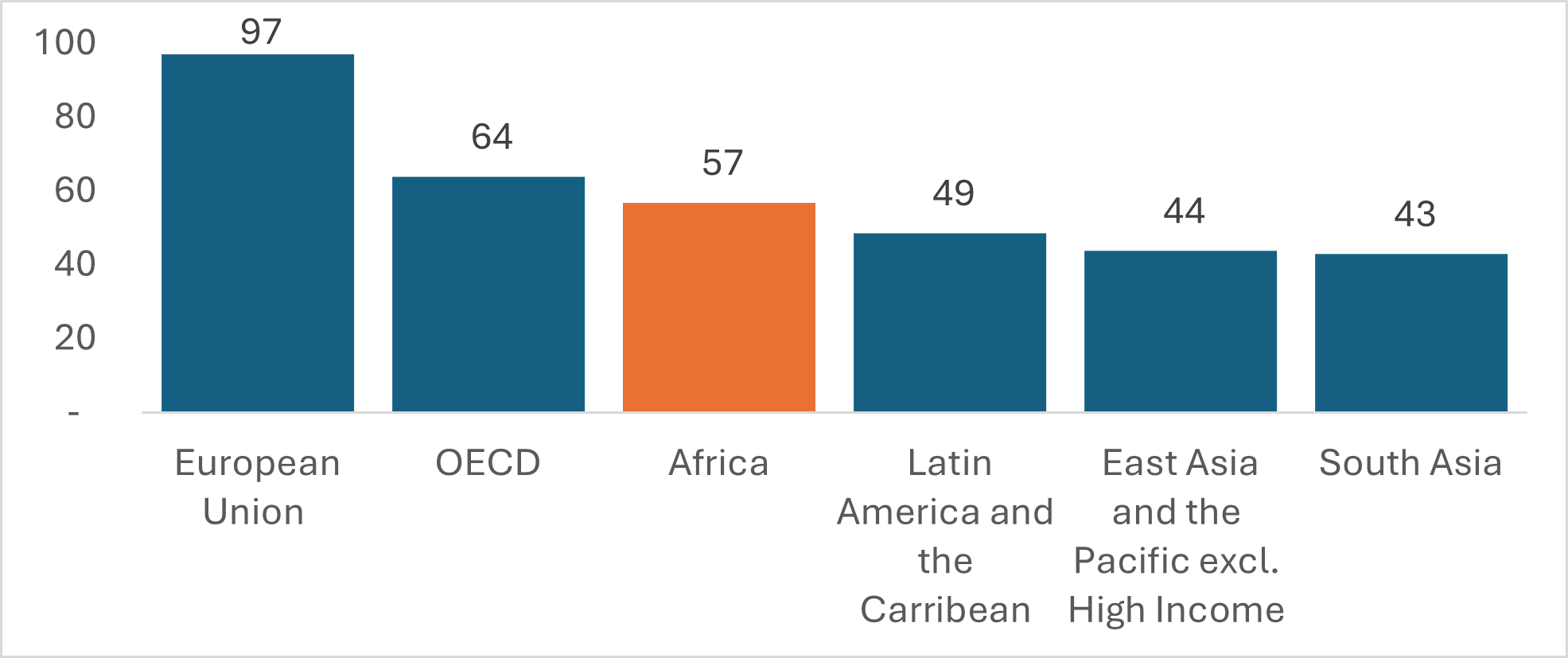

African countries, like emerging markets in other regions, have a way to go in terms of harnessing the potential for trade and development. Its trade relative to GDP is small in comparison to economically integrated and developed economies, such as EU countries, supporting the view that African markets have not fully harnessed the potential of trade-related growth.

Figure 2: Trade as a percentage of GDP, latest figures

Source: World Development Indicators, https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators

In addition to constraints around enabling trade, including physical infrastructure, competitive productive capacity and low institutional barriers to deliver both goods and services, the ability to make payment for traded products is a key enabler of trade. For a large mining company with operations across the globe like Rio Tinto, a 1% foreign currency cost would be 5.3% of its net profit to shareholders in 2023.[12] For Toyota, that share would be almost 9%.[13] In the case of Africa’s largest retailer, Shoprite, that share rises to 36%.[14]

The evolution of foreign currency exchange marketplaces

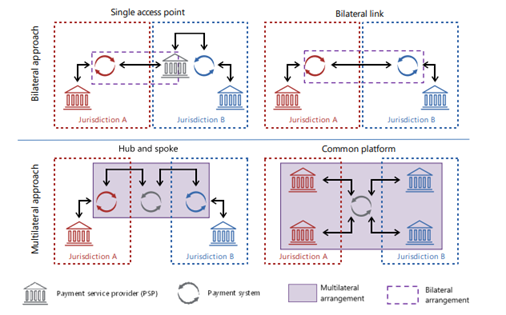

In a recent Bank of International Settlements paper, four stylized models are identified, as shown in Figure 3. The most complex, but efficient, foreign currency payments model, a common platform approach, offers a multilateral foreign currency exchange marketplace where countries can convert their currencies on a bilateral basis (i.e., a currency pair) between jurisdictions. However, this type of model requires countries to agree on a common platform, rules and risk management approaches for currency conversion.

The simplest model, the bilateral approach, with single-point access for foreign currency conversion, offered the greatest amount of control for central banks in Africa. This allowed African countries to intervene in currency markets to prop up their currencies by restricting access to other currencies. However, there was also the impact on the variety of currencies that could be efficiently exchanged.

Figure 3: Stylized currency exchange models

Source: BIS, https://www.bis.org/publ/work1094.pdf

Small African central banks have lacked the capacity to actively participate in all potential markets for their currency, by locating themselves in all the major offshore currency trading hubs. To solve this, they partnered with a small number of global correspondent banks that offered to act as an intermediary in all those markets for the central bank or leaned on ex-colonial masters or a regional economic leader to fulfill convertibility through currency pegs. The most successful of the latter two options are the two CFA regions pegs to the French Franc and now Euro and the Common Monetary Area in Southern Africa.

As the number of correspondent banks declined, so did the number of active currency corridors, where foreign currencies were traded regularly, with African countries being the most impacted region globally. This has meant that central banks effectively limited access to a wide range of currency pairs by partnering with a small number of global correspondent banks located mainly in the G7 countries and more recently China. This limited the number and way in which currencies could be converted efficiently to the correspondent banks’ own banking networks and interposed a trilateral currency exchange mechanism.

The remaining correspondent banks being overwhelmingly headquartered in the largest economies of the G20, have increasingly implemented conflicting regulatory requirements on the networks of banks operating in their markets, including the global correspondent banks. These conflicting regulatory requirements have peaked as Russian, Chinese and emerging market entities have been sanctioned for enabling Russia’s war in Ukraine and trade between Russia and Africa has also grown.

But the most significant impact has been to strangle access to financial services, especially in Africa. In a recent review of trade finance in West Africa, the International Finance Corporation (IFC) highlighted the impact a correspondent bank reliant on foreign exchange and trade finance market had on trade flows to large economies in West Africa.[15] Trade was estimated to be US$39 billion lower than it would have been if the market operated to global marketplace cost and accessibility standards.

As the global market for currencies fragmented due to the implementation of financial sanctions by the G7, the efficiency of the correspondent banking model has declined sharply. This has been compounded by the growing importance of China and more recently Russia in Africa’s trade relationships, which is bifurcating local banking services between those that can and those that cannot serve trade and capital flows from those countries.

The trend towards free convertibility has increased optionality

Geopolitical tensions spilling into global foreign exchange markets have coincided with changes to the way in which African markets are managing their currencies. While the current best practice recommended by global development finance institutions is to enable unhindered conversion of currency (via a free-floating convertible currency or a fully convertible currency peg)[16] with limited central bank intervention, the power of currencies to influence economic activity has tempted African central banks to intervene in currency marketplaces to achieve short-term policy goals that had a negative impact on longer-term financial sustainability and stability.

In 2018, seven African countries had their own free-floating currencies with a further 18 countries maintaining hard currency pegs. The balance of countries maintained a range of currency exchange models that facilitated central bank meddling. Since then, several large African economies, including Egypt, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Kenya and Angola have had to float their currencies, in part due to a combination of economic shocks driven by:

- Unsustainable borrowing by governments in foreign currencies that resulted in rising interest payments in foreign currency.

- Unsustainable currency interventions by central banks and governments that ran down foreign reserves, reducing the ability to meddle in foreign exchange markets.

- The rising damage to economies, and other non-currency interventions, such as rationing foreign exchange or not allowing for payments of certain trade items had on economic growth necessary to cover rising interest expenses.

- Withdrawal of donor funding, a key financial contributor to real exchange rate appreciation across Africa.[17]

- And finally, once economies defaulted on their foreign debts, the conditionality imposed by sovereign creditors to support the restructuring and repayment of countries’ financial obligations.[18]

This coincided with commitments by African countries to integrate economies under regional and continental trade blocs, most recently the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). This increases the need to migrate to a more cost-effective exchange of currencies between African states to take advantage of the expected windfalls from the large trading bloc.

Trilateral currency conversion is becoming economically untenable

As African countries have grown the share of regional trade to total trade, the need to diversify away from currency corridors supported by correspondent banks has grown.

Figure 4: Foreign currency exchange market segments

Source: BIS, World Bank, Cenfri, FSB, G20, OECD, UN, SSATP, UNCTAD and UNCTAD

African currency conversion costs remain the highest globally. In a review of remittance costs between African nations, the average cost recorded for all corridors was 8.5%, well above the global average cost of 6.35%. Within corridors, the range of costs is significant, with the lowest cost being 1.5% and the highest almost 24%, as shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Average costs to remit $500 in Q1 2024, World Bank[19]

| Receiving countries | |||||||||||||||||

|

Angola |

Botswana |

Kenya |

Lesotho |

Malawi |

Mali |

Mozambique |

Namibia |

Nigeria |

Rwanda |

South Sudan |

Swaziland |

Tanzania |

Uganda |

Zambia |

Zimbabwe |

||

|

Sending countries |

Angola |

8.6 | |||||||||||||||

|

Cameroon |

9.4 | ||||||||||||||||

|

Côte d’Ivoire |

2.0 | ||||||||||||||||

|

Ghana |

5.7 | ||||||||||||||||

|

Kenya |

5.1 | 6.4 | 6.4 | 6.4 | |||||||||||||

|

Rwanda |

11.0 | ||||||||||||||||

|

Senegal |

1.5 | ||||||||||||||||

|

South Africa |

9.0 | 10.1 | 7.7 | 7.6 | 4.5 | 7.3 | 10.2 | 7.2 | 8.5 | 8.8 | 8.5 | ||||||

|

Tanzania |

23.9 | 13.6 | 17.3 | ||||||||||||||

Remittance flows attract the highest costs of all foreign currency trades in Africa. However, it is rare for transaction costs to reach sub-1% conversion levels for retail transactions set as the target for forex payments by the G20. As a result, the pressure to enable bilateral currency corridors between African countries continues to grow.

How is Africa progressing towards enabling regional bilateral currency trade?

Africa has been proactive in trying to solve the cost of foreign currency exchange. The size and diversity of the continent and different starting points have resulted in different approaches to solving cross-border payments, potentially creating friction as payment mechanisms converge in the near future.

In the most recent survey of instant payment systems in Africa, SIIPS 2023, identified 5 cross-border payments systems in various stages of deployment. In addition to those is REPSS, a multilateral settlement system used by banks in COMESA to enable end-of-day payment settlement.

| Date launched | Type | Ownership | Segment coverage | Bilateral currency settlement | |

| Onafriq (prev. MFS Africa) | 2009 | Hub and Spoke | Private | Retail, Remittance | N/A |

| SADC-RTGS

(& TCIB) |

2013 (2021) | Common Platform | SADC regional trade bloc | Wholesale (and later business, retail and remittance) | Trilateral (South African Rand) |

| REPSS | 2016 | Hub and Spoke | COMESA trade bloc | Wholesale | Trilateral (USD, EURO) |

| GIMACPAY | 2016 | Common Platform | BEAC | Business, retail and remittance | Single currency used |

| BUNA | 2020 | Common Platform | Arab Monetary Fund | Wholesale, business, retail and remittance | Tri and bilateral depending on corridor |

| PAPSS | 2021 | Common Platform | AfrExIm Bank | Wholesale (2023), Business, retail and remittance | Bilateral |

| In Development | |||||

| COMESA IPS | TBC | ||||

| EAC IPS | TBC | ||||

| ECOWAS IPS | TBC | ||||

| WAEMU IPS | TBC | ||||

The start of the process of integrating national payment systems is closely correlated with the advent of Mobile Wallets. In fact, Onafriq (MFS Africa) was founded by an MTN Mobile Money business development officer as he was launching MTN Mobile Money across Central and West Africa and found the solution was not able to integrate multi-wallet payments and cross-border remittances. MTN (Africa’s largest mobile network operator) is now the largest financial services company in Africa by number of customers served, in part due to MFS Africa’s ability to boost diversity of payment use cases beyond those MTN was allowed to offer by regulators.

The establishment of Onafriq was followed by the launch of SADC-RTGS, with a focus on integrating banks (rather than telco wallets) across the SADC region. The platform operator, Bankserv Africa, was already operating the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) payments network for the large member banks, based in South Africa.

RTGS systems support large-value payments. Member banks were able to engage in intra-day transaction netting, allowing commercial banks to reduce their exposure to local currencies and reduce the amount of pre-funding needed to execute foreign currency transactions. However, this more efficient settlement system did not translate into lower retail and remittance costs for customers, as illustrated by the high costs still faced by remitting customers from South Africa to other SADC markets.

REPSS and GIMACPAY addressed different issues faced by their member countries. REPSS aimed at delivering more secure settlement with the aim of improving trade flows amongst COMESA countries. Again, the focus was on delivering a large value payments solution, which addressed the narrow issue faced by banks, but not their customers.

GIMACPAY’s focus was on medium and low-value payments. The platform enables digital payments using multiple payment instruments across the single currency Central African CFA region, much like SEPA has achieved in Eurozone countries. While creating a more efficient mechanism to pay across the CFA region, the platform is not well suited to enabling multi-currency payments.

The more recent initiatives have broadened the ambition of foreign currency payment enablers by addressing higher-cost multi-currency retail and remittance payment segments in the medium and low-value segments. PAPSS, BUNA and SADC’s TCIB offer a way for bank users to access instant cross-border payments as well as reduce the foreign currency exposure of participants.

Concluding remarks

Africa’s foreign currency payments landscape is changing fast, but not just because it has kept geopolitical commentators busy. The combination of technology, informalization of foreign currency payments, and the rising costs of leveraging G7 bank infrastructure to enable foreign currency exchange has been pushing African regulators and financial services participants to leapfrog legacy foreign exchange models that have been the mainstay of currency exchange in Africa since independence.

Much as the mobile phone enabled connectivity to Africa when fixed lines were not affordable, the implications of the leapfrogging of mature market models are yet to be felt as the last leg of deploying instant payment platforms that reach end users is yet to be fully deployed. However, if the experience of Africa’s journey towards driving digital connectivity is anything to go by, the impact is likely to be profound, resulting in higher rates of trade, investment and regional economic integration between instant payment networks across Africa and in other regions, like the Middle East.

Payments remain a gateway to further financial services. To maintain momentum, regulators and financial services businesses will need to start thinking about how to unlock other critical financial services market opportunities, from trade finance to developing capital markets. After all, globally competitive foreign currency exchange marketplaces are a key enabler to financial sector development and financial sector profitability.

[1] Mathias Drehmann and Vladyslav Sushko, “The global foreign exchange market in a higher-volatality environment,”BIS Quarterly Review, December 5, 2022, https://www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf/r_qt2212f.htm.

[2] Foreign Exchange Market Size & Share Analysis – Growth Trends & Forecasts (2024-2029), https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/foreign-exchange-market; https://www.technavio.com/report/foreign-exchange-market-industry-analysis.

[3] “An Analysis of Trends in Cost of Remittance Services,” Remittance Prices Worldwide Quarterly, Issue 49, March 2024, https://remittanceprices.worldbank.org/sites/default/files/rpw_main_report_and_annex_q124_final.pdf.

[4] “Powering Growth with Curiosity: Annual Report 2023,” J P Morgan Chase & Co., https://www.jpmorganchase.com/content/dam/jpmc/jpmorgan-chase-and-co/investor-relations/documents/annualreport-2023.pdf.

[5] “Sovereign wealth funds are playing an increasingly important role in global development,” World Economic Forum, November 6, 2024, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/11/sovereign-wealth-funds-are-playing-an-increasingly-important-role-in-economies-everywhere/#:~:text=Sovereign%20wealth%20funds%3A%20the%20%2411.3,tenfold%20in%20the%20last%20decade.

[6] “Shipping from South Africa to China,” Ship Hub, https://www.shiphub.co/shipping-from-south-africa-to-china/#:~:text=Ocean%20shipping%20from%20South%20Africa,weather%2C%20or%20even%20customs%20clearance.

[7] “The Bretton Woods System,” World Gold Council, https://www.gold.org/history-gold/bretton-woods-system#:~:text=The%20Bretton%20Woods%20system%20was,exchange%20rates%20to%20the%20dollar.

[8] “David Cook and Nikhil Patel, “Dollar invoicing, global value chains, and the business cycle dynamics of international trade,”BIS, no. 860, April 28, 2020, https://www.bis.org/publ/work860.htm.

[9] Benjamin J. Cohen, “The Future of Reserve Currencies,” Finance & Development 46, no. 3 (September 2009), International Monetary Fund, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2009/09/cohen.htm

[10] “Emerging Markets,” World Economic Forum, September 2024, https://www.worldeconomics.com/Regions/Emerging-Markets/#:~:text=World%20Economics%20has%20combined%2024,years%20(2013%2D2023).

[11] Sir John Cunliffe, “Enhancing cross-border payments: building blocks of a global roadmap,” BIS, July 13, 2020, https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d193.htm.

[12] “Annual Report: 2023 year in review,” Rio Tinto, https://www.riotinto.com/en/invest/reports/annual-report.

[13] “Financial Summary: FY2025 First Quarter,” Toyota Motor Corporation, August 1, 2024, https://global.toyota/pages/global_toyota/ir/financial-results/2025_1q_summary_en.pdf.

[14] “Unaudited Results for the 26 Weeks Ended 31 December 2023 and Cash Dividend Declaration,” Shoprite Holdings Ltd, https://www.shopriteholdings.co.za/docs/int2024-mar2024.pdf.

[15] “Trade Finance in West Africa,” International Finance Corporation, October 2022, https://www.ifc.org/content/dam/ifc/doc/2022/report-trade-finance-in-west-africa.pdf.

[16] Rodrigo Heresi and Eric Parrado, Trade Openness and Exchange Rate Management, IADB, December 2023, https://publications.iadb.org/en/trade-openness-and-exchange-rate-management.

[17] Ahmad Hassan Ahmad, Eric J. Pentecost, Marie M. Stack, “Foreign aid, debt interest repayments and Dutch disease effects in a real exchange rate model for African countries,” Economic Modelling 126 (2023),

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2023.106434.

[18] Laurent Kemoe, Moustapha Mbohou Mama, Hamza Mighri, Saad Quayyum, “African Currencies are Under Pressure Amid Higher – for – LongerUS Interest Rates,” IMF Blog, May 15, 2023, https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2023/05/15/african-currencies-are-under-pressure-amid-higher-for-longer-us-interest-rates.

[19] The World Bank, “Remittance Prices Worldwide,” July 6, 2024, http://remittanceprices.worldbank.org.